One of the speakers at the conference was Brenda Lintinger, a speaker of Tunica-Tulane, a native north American language from Louisiana whose last fluent speaker died almost fifty years ago. She commented that her tribe never likes to consider their language dead, but rather, sleeping.

I was thinking later about the difference between sleeping and extinction. In the first case, there is hope against many odds that someone could wake the language up, and despite major changes in surroundings, it could be brought to life again. Hebrew in Israel, on a massive scale, and Wampanoag in Massachusetts, on a small scale, are two modern cases of such efforts. If you ever saw Woody Allen’s movie “Sleeper” you know it is hard to wake up and find yourself a big chunk of years in the future. Suppose your people were hunter-gatherers, who never had wheels except as sacred objects, and never built any lasting structures, but instead followed the movements of animals and crops with the seasons. You were still fully human, with deeply developed human culture and language, but modern people know little about your life because you didn’t leave much of a written or architectural record, or because the Europeans who first met you overwhelmed you with disease and war.

Now, you wake up in the 21st century with cars, internet and the weight of post-Bush America all around you. Casinos are big – your people may be able to build one, having some slim legal claim to sovereignty, but these casinos devastate the environment and prey on addictive tendencies in some individuals. Furthermore, because of the special legal status of your ethnic group, there is an enrollment period to prove you are a member of the tribe, and those who don’t sign up are not legally allowed after a certain cutoff date to benefit from the casinos. In this imaginary scenario I am mixing up the experiences of a number of different indigenous groups currently alive in what is now called New England, but the threads are real ones indigenous people have described to me and written about.

Against all these odds, languages and cultures can be revived. And the people who do reclaim their language and culture often describe a renewed sense of history and connectedness. The Tunica-Biloxi woman at the conference read an opening prayer in her language for all of us, and said that even though she is not certain how it used to be pronounced, she finds that just knowing the meaning of the words and saying them out loud allows them to roll off her tongue and experience a confidence that the phrasing will come naturally.

Fox News Latino article features our project

To see someone else’s review of our project, check the following website

http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/health/2011/08/25/effort-to-save-endangered-languages/

This year’s Yachay Q’ipi

My blog has been quiet recently as I spent my first summer home in four years! That doesn’t mean our native language documentation and revitalization project has come to a halt this year, though. Donations from friends helped my colleagues Martin Castillo Collado and Mary Carmen Bolivar mentor four itinerant teachers in rural Perú as they learned to use and develop thematic, hands-on activities in their respective schools to integrate children’s native language and culture with academic activities. Participating teachers attended introductory and planning workshops and then spent a day implementing their plans in the classroom under Martin and Mary Carmen’s expert observation. Project results will be reported at the Foundation for Endangered Languages Conference in Quito, Ecuador and at the Symposium on the Teaching and Learning of Indigenous Languages of Latin America, Notre Dame University, Indiana this Fall. Most importantly, the teachers formed a group to continue supporting each other in native language activities in their schools.

The photos to the right show children using traditional Quechua hand measurements to measure their height, recording observations in their native language, bags of beans and potatoes for experiments in estimation, and kids playing at buying and selling. It has been a thrill seeing the activities we envisioned and piloted last summer fleshed out in new contexts.

I’ll be leaving for Bolivia myself in less than three weeks to continue the work there.

Oven can be a verb

A few years ago an anthropologist friend remarked that in the Central American language he was studying, “housing” was a verb, never a noun, and houses always seemed to be growing and changing to fit the families that lived in them. Last week in Ccotatóclla I saw that ovens could also grow and change radically in the course of preparing a meal. I tend to think of ovens as static objects with occasional moving parts. I had never seen someone break a hole their oven to convert it into a stove, or mix cement right on the spot to seal openings in the oven.

It was my compadre Ignacio’s birthday and he wanted to make a chicken and potato roast for his extended family; some of his twelve siblings and their families might stop by for lunch. His mother came over to peel several large pots full of fresh and freeze dried potatoes with his wife and me.

I went outside to take a look at the wathiya, or earth and stone oven he was preparing. It was a long, hardened clay dome right next to the pig pen. He put some branches inside to start a fire, then began hacking at the top of the oven with a pick axe. I was sure he would destroy his oven, but he only cut a hole in the top and placed a large pot of potatoes on it to catch the escaping steam and smoke from the fire inside.

Meanwhile, the burning branches got hotter and turned to coals after about a half hour. I came back outside from peeling more potatoes and noticed that Ignacio had chopped up the ground immediately in front of the stove and was pouring water and mixing the dirt with a shovel to make a thick muddy cement.

When the potatoes were boiled and the branches turned to charcoal inside the oven, Ignacio removed the pot and placed a bunch of rocks over the hole in the top of the oven. He shoveled some mud onto the rocks to seal the hole.

Elena and I had cleaned the chicken and marinated it in a ready-made sauce that the chicken vendor had brought to the house with the meat. Ignacio had washed a piece of corrugated tin and bent it like a giant tray; now he poured cooking oil on it and we placed chicken and potatoes on the tin. He and Elena quickly shoved the tray inside the oven and sealed it with a large rock and more mud.

The earth-oven was sealed tight and we waited another half hour for the chicken and potatoes to roast.

I am not sure which was more wonderful: the aroma of the chicken when it came out of the oven, or the way in which the oven was broken apart, converted into a stove, re-sealed with mud and finally opened again so we could eat.

One of the children quickly wrapped some of the food to share with her uncle’s family next door. I was surprised that no one but Ignacio’s parents and immediate family came by for the feast. He didn’t seem too upset; he said maybe the others hadn’t been able to get up the road due to construction.

For the rest of the afternoon he asked me to shoot photos of himself and his family in traditional clothing, posing outside the house. He wanted some for his daughters to remember this time with, and also a whole series for a political campaign his is about to undertake. After that, he sat down by the fire to tell me stories in Quechua. Elena sat next to him, spinning lamb’s wool into yarn with a simple wooden spindle that looks like a disk with a stick at its center.

That evening several local community leaders stopped by to discuss strategies for their own political campaigns. The rest of the leftover chicken disappeared fast.

A taste of Quechua

Photo: Ausangate viewed from Ccotatóclla

I will be back to visit Ccotatóclla but not necessarily to live for as long as I did this year.

Every time I smell wood smoke I remember the hearth of Elena and Ignacio’s home. Here is a handful of the sentences I said to them in that room:

Susanpa ayllun

Sutiyuqmi Susan. Taytaypa sutinmi Charles. Mamaypa sutintaq Nadine. Kimsa ñañaturayuqmi kani, ñuqawan tawan kayku: iskay warmi, iskay qhari. Judith, Thomas, Susan, Andrew. Qusaypa sutinmi Josh. Ñuqaykuqa isaky wawayuqmi kayku: huk warmi, huk qhari. Paykunan Sylvie, Jacob ima.

Susan’s family

My name is Susan. My father’s name is Charles. My mother’s name is Nadine. I have three brothers and sisters; with me there are four: two women, two men. Judith, Thomas, Susan, Andres. My husband’s name is Josh. We have two children, one girl, one boy. They are Sylvie and Jacob.

Here are some things Elena and family taught me to say:

Munay pilliminayki. – Your hair-ties are cute. (she wants me to get some for Yeny)

Munay chumpayki. – Your sweater is cute.

Mana ñachu yapata munayki? – Don’t you want more?

Wiksaymi askhata mikhuqtiyqa nanawanman. – My belly will ache from eating too much.

Mikhuchkani ciwada lawata. – I am eating barley soup.

Ayihadachay Yeny wasinpi tiyachkani. – I am living with my little goddaughter Yeny.

Ch’iqtachkan. – He is chopping wood.

In standard Cusco Quechua, mallki is tree and mallki mallki is forest; here, mallki is only a bush and sach’a is a tree; sach’a sach’a is a forest.

Quechua is an interesting language for an English speaker! It´s directionality runs backwards from ours; (like Japanese or Turkish) the subject comes first, but then come indirect objects, direct objects, and finally, the verb. There is no verb ‘to have’ but having is often marked with case markers on the noun (as in -q or –paabove.) Most sentences mark whether the information was witnessed by the speaker (as in -mi above) or reported from another source.

Quechua speakers like to tell others who are learning their language that it is an especially onomatopoetic language, meaning that many of its sounds come from nature, and an especially tender and spiritual language; there are many emotive and intensifying suffixes that relate the speaker to the hearer, and physical entities such as rocks, wind and trees are addressed as if they were feeling beings.

Clausura – Closing ceremony

Photo: Sue with teachers and community members

The night before our project’s closing ceremony, I laid out my clothes and reminded ten year old Sudit and her parents that they were invited to wear traditional clothes for our Friday morning celebration.

They seemed very hesitant about it, so I told them Alejandro Galiano would be there, and I showed them videos of local kids reading aloud in Kucya that I had filmed the day before. They were thoroughly engaged and wanted to watch as child after child read aloud.

Elena went upstairs and came down with her traditional pollera (a black skirt covered with a combination of store-bought and homemade embroideries and weavings.) She modeled her montera for me ( a large, flat hat with wool trim and home-made beaded chin straps. I asked where I could buy a traditional pollera and she said in Huancarani but it would cost at least 1000 soles or more than 300 US dollars. She has had hers for nearly twenty years. Sudit came down wearing her own traditional pollera which was a bit small, and everyone started to dance. Then they wanted me to try the pollera on, and dance.

Elena said I should wear the pollera to school on Friday. I said I would be proud to, but would rather have her there to wear it herself.

In the morning, she insisted she would not go; she would be embarrassed. I asked if I could offer the pollera to the teacher Margarita to wear, since I would mostly be filming and not speaking.

Friday morning, it looked like Margarita was not going to put it on, since she claimed she lacked the proper shoes. But five minutes before everything started, there she was, wearing the pollera.

Alejandro, his flute player Ramiro, and Martin all arrived around 7:30 am. Kids showed up at 8:30 and a handful of parents; we made a large circle of chairs outside, played some music and gradually more townspeople began to show up. At first only two or three kids were wearing traditional dress, but in the course of an hour, adults and children alike seemed to appear from nowhere in traditional dress.

Children read some of the stories they had written during the project. Others told riddles and read aloud from books. Adults spoke about the project, including myself. I said: “Teachers will tell you they are there to teach, but really they are there to learn. Thank you for teaching me about the things that live in your schoolyard and your town these past weeks…They say that there are three thousand languages in danger of extinction within our lifetime; please do not let Quechua be one of them.”

Alejandro spoke about native language education and thanked my research group for its three year study of child Quechua in the region. Martin spoke, and my compadre Ignacio put on traditional dress in order to speak on behalf of the Town Council. He gave a brief history of the town, which he said was originally settled by people who spoke Aymara, a language that is different from Quechua but has been in contact for centuries. Ccotatóclla means “Scarce water plain” in Aymara.

At the end, the drummers and flute began to play; Margarita and others started to dance with me, and the next thing I knew, someone was dressing me in traditional clothing for more dances. We danced and danced until it was time for lunch; I went back to pack and say goodbye to my hosts. Elena and Sudit cried and said they thought I wouldn’t return, but I reminded them that I would be back with my daughter and niece in less than a month.

I caught the teachers’ van at 2:00 pm and we descended the dirt road for the next three hours, ending up in San Jerónimo just before dark. Martin and I headed to his home; I went to call my family and he was off to teach a series of weekend workshops in an even more remote rural village by 8:00 pm.

Golden worms

Photo: Two girls on the playground

This post is for my siblings. Our Dad (aged 88) is sick and having a rough summer. I just want them to know that one night we were telling ghost stories at Ignacio’s house and I told Dad’s story of the golden worms, from our childhood. In the story, any children in the room are named as protagonists and go off in search of golden worms at a haunted house. The punchline comes when they find themselves with their hands in a bowl of spaghetti…

I adapted the story for Ignacio’s kids and he retold it in Quechua, complete with sound effects, which I have captured on MP3.

How do you think Dad would like that?

Not for the faint-hearted

Thursday, July 22

I am fifty years old and have eaten meat all my life. However, I have never killed my food or seen it killed for me (except a fish my grandfather made me bait, catch and clean when I was nine.) I know that my grandmother used to know how to pluck a chicken or turkey, but I don’t think my mother ever had to do that; all of our meat was butchered and packaged for us. Today my comadre Elena announced she would prepare meat for us; the first meat we have eaten since I arrived. She had her ten year old daughter start a fire and boil water on one side of the clay oven; steam a pot of potatoes on the other.

Then she killed one of the seven guinea pigs that live on a straw bed and underfoot in their kitchen. She chose one of the three mature ones (not the pregnant one) and strangled it within less than a minute. She dipped the body in the boiling water and began pulling off the hair into a plastic basin, paying special attention to cleaning ears and eyes with her fingers. Once the carcass was free of hair she took it outside to a sink and continued stripping off all hairs with a knife. Then she opened a hole in the lower belly and emptied all the guts into a bowl.

She prepared another bowl with garlic, cumin and mint or bayleaf, a little water and a lot of salt which she ground with a fist-sized stone. Once the main meat parts were cut up she dipped them in this sauce and deep fried them on her clay stove. The little girls came to watch.

While all that was cooking she began to deal with the viscera; I asked if these would be for the pig. “No! These are nutritious for us!” she said. She first rinsed the liver, lungs and heart. Then she removed all the pellets from the intestine and took all the intestinal parts and stomach outside to empty and rinse. She would not waste a single edible part of this tiny animal. They are marinating now in the sauce while she fries up the steamed potatoes.

I ate roasted guinea pig the other day and it tasted like bacon. You just have to watch out for the tiny bones.

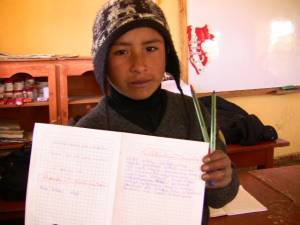

Impact at school

Photo: Boy with notebook, Ccotatóclla

Written Thursday, July 22

What impact can our small project have at the school? In a ten-day period, class has been cancelled for the kindergarten 3 days so that the kindergarten teacher could attend two trainings and a festival. The 3rd-4th grade teacher has been out sick seven days, with no sub to be found, so Martin and I each spent a day teaching her class. The 1st-2nd grade teacher took two days off (for training and festival.) The director, who teaches the 5th-6th grade class, was only out one day (for the festival) but frankly her instruction left the most to be desired; she tends to write potentially helpful things on the board with no explanation or integration; the kids’ homework makes no sense and gets nothing but a rubber stamp.

This high level of instability leads to choppy instruction, and our project was already going to be very short-term even if we had had ten complete days to realize it with the help of fully engaged teachers.

Still, we have piloted our first hands-on, Quechua language curriculum kit, and I think we have accomplished a couple of important things for teachers and kids.

The most important thing is, I persuaded the youngest teacher to leave the teacher’s compound and have supper with the family that is hosting me. The teacher and my comadre chatted in Quechua for hours about everything from school to personal life. Afterwards she told me she realized that making connections with the townsfolk could really transform her work. Too often, teachers who come in from the outside stick to themselves and see the parents as adversaries. The most successful native language instructor in the area has shown that when teachers cultivate alliances with community members, everyone benefits.

We took the youngest teacher out walking in the mountains and shared many meals together. I videotaped a model class with Martin leading activities, and then videotaped the youngest teacher so she could critique her own work, which she watched with great interest.

The second most important thing is, we spent four intensive days in two of the classrooms, engaging kids in outdoor experiences which they then wrote and read about in Quechua, in a variety of modes (lists of things found, words to describe the feeling and smell of the things when hidden from sight; numbers, dimensions and dates, stories made up by groups and individuals on the spot.) One day was simply spent listening to kids read aloud from their journals and from books in their native language. I showed the kids a video of kids from the next town over reading aloud from books (where native language education is thriving) wearing their traditional clothing as they do for the three days per week when instruction is in Quechua. The kids in Ccotatóclla were dying to show that they, too, can read in Quechua, and they were dying to get their hands on books in their native language, which they borrowed, read cover-to-cover and returned. Martin and I brought along a dozen books for them, but more importantly we told the youngest teacher how she can get more from the Ministry of Education.

Tomorrow is the closing celebration of our project and we have invited children to come with their parents, dressed in traditional clothing, to read from their journals and books and celebrate our project together, and to be photographed and videotaped.

Pasantía – Peruvian teachers´ in-service training

Photo: Alejandro Galiano, Martin Castillo, Ramiro Zúñiga

On Wednsday, right in the middle of our final week of the project, the 1st-2nd grade teacher (Margarita) was told she needed to attend a day-long training at a school in the nearby town of Kucya. She invited me to come along.

Martin had taken Margarita and me to a mountaintop Monday and pointed out which direction we would need to hike in order to reach Kucya. She and I started out just after dawn, made our way through the fields, orienting ourselves toward a house used for radio transmission on one of the mountain tops. We knew we were supposed to go to the north of that mountain and down around the south side of another mountain to get to Kucya. We weren’t on any trail for parts of the trek but gradually found our way down to Kucya and confirmed with schoolchildren hiking up the pass that we were heading in the right direction.

The hike itself was pure joy for me as several of my friends have told me many stories of wandering through these Andes as itinerant teachers. I always wanted to do it, and we did it!

The day was also a tremendous boost for my morale. I was included in a group of about 15 novice rural teachers as we watched a local master of native language instruction work in a first grade class for a full day. There were periods of time for questions and answers, reflection, debate, but mostly we just watched this master with his class.

The school is in an especially arid place and has no electricity. I recognized the master teacher (Alejandro Galiano) as someone I had met three years ago as part of a Quechua-language curriculum design group. The really dedicated, hardcore teachers all tend to know each other and support each other in various groups and associations. Alejandro invited the novice teachers to join these groups; he made it clear that there is no closed circle and that new energy is needed.

The first outstanding things about this teacher is, he speaks Quechua in class, insists on wearing traditional dress, carries a bag of coca with him everywhere, offers alcohol to the mountain gods for their protection, sleeps in the country folks’ homes and knows them all as friends and allies. Even the most cynical townspeople around the region speak of him with great respect.

The second outstanding thing about him is, he works day and night on every lesson he teaches, and clearly adores the kids. He does not raise his voice or humiliate children or adults. Young people in Kucya have begun to flock to him and his colleagues, begging to learn to read and write in Quechua, because they recognize that what they speak is in mixture of Quechua and Spanish. Elders in town are honored as guests and sages in his classes and are engaged in recuperating their language and culture for the next generation. Alejandro has teamed up with a quena player (reed flute player) and there is frequent music and dance in his class.

All schools in the Andes seem to start with Catholic prayers and recitations of national creeds; Alejandro’s class includes a morning ritual of holding up three coca leaves and asking the local mountain gods and Pacha Mama (Mother Earth) for assistance in being good people and good students.

Alejandro has been teaching for eight years; he pursues 80% of his instruction in Quechua and 20% in Spanish. His students have done well on national tests and have gone onto excel in professional and university settings. For this reason he has been identified by the Ministry of Education as a master teacher and now is charged with visiting schools in his region to improve native language instruction.

A humorous note…one of Alejandro’s practices has been to engage local artesans in teaching their specialties to children, and he wanted the kids and their families to sell their products to tourists passing by in order to raise funds for the school. Since the community is extremely arid and poor with no tourist attractions to speak of, he and some friends looked closely at ancient ch’ullpas (funerary towers) in the neighboring town of Ninamarca and decided to build some replicas themselves of local materials. They built the ch’ullpas in a matter of several evenings on a hillside and began selling their weavings and crafts projects to tourists passing through.

The National Institute of Culture (INC) was horrified; the ch’ullpas came out so authentic-looking that Alejandro and friends were first accused of having stolen them and rebuilt them on a different site. They were called to a series of meetings to defend themselves and were ultimately instructed to destroy the ch’ullpa replicas or face jail time. Meanwhile, the Marriott Hotel chain is apparently destroying actual Inca structures in the center of Cusco in order to build a monster tourist trap – no trouble from the INC there.

I took some nice photos of Alejandro’s ch’ullpas…every time they are told to destroy them, they call out the press and nothing seems to happen.

Alejandro wanted to see for himself what was going on at the school in Ccotatóclla, so we invited him to attend our project’s closing ceremony on Friday.