Written July 9

It is very exciting here in the countryside today is my fourth day here and I am typing from the school office. My compadres have been very open and friendly with me and have made it clear that they want me to be comfortable and to feel like we are family. Later this afternoon I will meet with the teachers and propose a day-by-day schedule for our curriculum project to start next week. We will call a parent meeting for Monday night.

Yesterday Elena showed me her loom which is set up in the back yard and she is weaving a big heavy wool blanket from her own sheep’s wool which she dyed, spun and set up on the loom. The pattern is wide colored stripes, with large flowers and spiders. As she was weaving, I was sewing pockets on the apron I made for her. So we were just sitting there working in the morning sun and people started coming by to say hello and chat. One man was there for a long time, a man with a radio; it wasn’t until he left that I was formally introduced and I realized that he is the community president (umalliq.) I hadn’t met him last year because he was away; and Martin hadn’t met him this year because he was off campaigning for political office in the district. This morning they announced on the radio that he is an official candidate.

A few women passed through the yard in the morning on their way down to fields, I guess. Some stopped to chat.

The days have been so packed with new information that I am having trouble remembering conversations and who said what.

This morning Ignacio asked if I could start teaching English at the school and I said no, not during the day, it would supplant my main project, but I would be happy to give English lessons in the afternoon to anyone interested. He was really excited about that and said we should make it a kind of English-Quechua exchange. There is clearly a big interest in learning English here.

Yesterday with Elena and Ignacio we continued to talk about everything from household economics to birth control. They wanted to know what method we used (Ignacio translated ‘vasectomy’ in Quechua as cutting off a man’s balls, which we all chuckled about, although I was able to clarify…) Elena told me that she doesn’t want to have any more kids and her method is to “take care of herself” using the rhythm method, which she described.

I asked Elena what they do about personal hygiene and she said she puts sanitary napkins under a pile of hay and burns them, or throws them down the outhouse, which they put ashes in. She said her 10 year old daughter doesn’t know about menstruation yet and she won’t tell her until she gets her period. Tradition is to wait and tell a girl once her period starts. She says there is no reproductive education at school. She told me she has really painful periods with pain in her lower back and occasional pain in her ovaries (she thought she might have an infection in her ovary) I told her I have the same pain.

She wanted to know if North-American women feel pain during childbirth and I said yes, although some women have pain killers in the hospital. She had both of her births at home with no medical help but did have the help of her mother-in-law, with whom she gets along really well. Many women in the countryside give birth without medical help of any kind. She did have a baby girl who died or was born dead, a nice fat baby and I didn’t understand the reason for the death. She wants to have a boy but thinks it will never happen, and she won’t try again until her youngest, Yeny, is eight.

It was interesting, later during the course of the day I found out that Ignacio and Elena plan to move to Cusco in December so Sudit can go to secondary school there. Their fondest dream is for her to become a professional; perhaps a nurse; so she can maintain them in their old age. I asked about the farm and they said that she would not be able to sustain them on the farm. Everything is changing, they said, and you can’t make a living on the farm. There are increasing droughts and discussions of global warming on the radio. However, Ignacio says he prefers living in the country over the city and he says it is more relaxed.

They asked me about the Twin Towers (World Trade Center) and they were curious about how tall the buildings were, how many floors they had and what their destruction was all about. I gave a brief blow by blow account of the four planes that flew from Boston that day and explained it was a terrorist attack. Ignacio was surprised that the people who carried it out died in the attack and he wanted to know if the attack paralyzed the American economy or what it actually accomplished; I explained it was symbolic of hurting America’s economic power and also by hitting the Pentagon, the power to instigate wars. Ignacio said “your country has the most powerful military in the world, which makes you the most powerful” and I tried to explain the source of the US power; that the continent was colonized late by Europeans overflowing from their own lands and they found lots of land and resources in North America; and that people still come there for economic opportunity. He also wanted to know what the war in Iraq was all about and I explained it was a battle for control of the oil in the region, which US scientists initially discovered and then the locals wanted power over. It Is interesting to have these conversations where we can barely understand each other and we are speaking in enormous, sweeping over-simplifications and generalizations. Sometimes I wonder if the conversations are useful but in the course of the day and night it seems we are establishing something of a shared world view. They are explaining their world and their economics to me as well.

I feel they are sharing a lot of personal information about their family economics as well, and not just grilling me for my own. For example, I asked Elena if she goes to pasture her animals and she hung her head; first she said yes and then she said “I have no animals, only one sow.” It turns out that in order to buy the car a few years ago they sold all of their livestock. Then, the car failed as an investment because it was always needing repair and there was not enough income to cover the repairs, so Ignacio had to go in debt to a friend to pay for repairs, and now the car doesn’t even work. He says that his goal currently is to fix the car up and sell it. I asked if he would buy livestock again and he said it is expensive; a calf costs 500 soles; sheep are also expensive. They can’t tend animals in the city of Cusco. They had bought land there years ago and Ignacio built a home there for Sudit to have. They want to purchase land for each girl so each can have her own land and house. They want their girls to have a good education. Once the girls are through school they want to move back to their farm here in Ccotatócclla.

We talked a lot about the godparent relationship with them and with other people who stopped by. I explained that in my tradition I received godparents at baptism in my infancy. They were chosen by my parents. They didn’t have a financial relationship with me but rather a spiritual one and mostly just gave me a Bible and/or things to read, cards and gifts on my first communion etc.

Here, when I cut Yeny’s hair and gave her $20, they invested the money in a small sheep for Yeny (a hair growing animal to make up for her lost hair.) and they will sell the sheep at some point and keep investing the money on her behalf. Everyone wants to know if I will pay for Yeny’s education and bring her to live as my daughter in the states. I said I was doubtful about that but I will support her education in any ways I can.

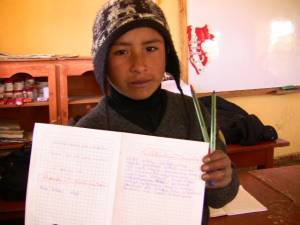

The girls and I went out for a walk yesterday afternoon. We found some slate by the side of the road and Sudit showed me how she uses it to write people’s names. She also picked eucalyptus and another roadside plant to make tea, which we had this morning.

The telephone is run as a business from someone’s home down the road and doesn’t accept my phone card. A 10 minute call cost 13 soles (a little more than $4 US.) Ignacio’s cellphone can’t make outgoing calls unless he charges it in Cusco. The nearest other phone is in Huancarani, an hour away by bus.

There have been a lot of traffic accidents lately and I want to minimize travel on that road. Accidents due to vehicles losing their brakes, landslides and reckless driving.

My health has been good, even my stomach. I caught a cold that was going around the first hotel I stayed at but it already cleared up. Both my hosts have a virus with snot, headache and fever; so far I don’t have it.